What's a lyric coloratura like me doing belting Sweeney Todd?

Read MoreMy Sunken Chest (Register)

I took traditional classical voice lessons from the age of 13, and I developed a great stratospheric head voice -- my natural range and easy for me to use. But, whenever the melody descended towards middle C, it got difficult for me. I noticed it when I sang solos and when I sang in my school choir. I just couldn’t figure out how to move from head voice to chest, let alone how to get back up. I carried my head voice down too far, and ended up with a tiny breathy low sound at the bottom of the staff. No one talked about it with me when they heard it, and I didn't know enough to ask.

When it was a matter of musical life or death and I had to be heard, I would shout and squeeze out the lowest notes in my chest voice. It didn't feel good, and it was more difficult for me to reclaim my head voice afterwards. Like anyone else with one overdeveloped range and one underdeveloped range, I had a noticeable break. I knew my chest voice and head voice were as different as Jekyll and Hyde, and it embarrassed me. So, I gravitated to songs that showcased my high range. I embraced opera and 1940s and 1950s girl singer repertoire. George Gershwin's "Summertime" -- in the original key -- was my jam! I loved Eydie Gorme and Peggy Lee, crooners who exhaled into the microphone, did not push or strain in chest register, and rarely ascended to head voice. The chanteuse Sade had a breathy dominant chest register, a big break, and an even weaker head voice. Ironically, that made it easier for me to imitate her so I became a big Sade fan.

In the absence of any instruction to the contrary, I convinced myself that I couldn't sing notes below a certain pitch. I might as well have admitted that I couldn’t turn left.

I spent a frustrating year in Shillelagh, my high school's show choir. I had auditioned as a singer, but my break and breathy low range was obvious. Then I made the mistake of showing our teacher Mr. Reardon that I could play keyboards, so naturally I became the keyboard player. I watched the backs of all the beautiful girls as they sashayed through each show, doing jazz squares in sparkly red leotards and black wrap skirts. Meanwhile, I was hidden behind the Yamaha DX-7, playing the accompaniment to “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” and "We Got The Power," keeping my mouth shut. I loved trying out new sounds on the keyboard and jamming with the rest of my bandmates, and I loved getting out of class to play for the Christmas parties of local businesses. But I wished I could sing with them, and sing like them.

Mr. Reardon was a fan of vocal jazz, so Shillelagh performed a lot of songs originally recorded by The Manhattan Transfer. All the performing girls were invited to audition for a short alto solo in "Birdland". I begged to be allowed to try out, too, and after a lot of pleading, Mr. Reardon relented. I memorized Janis Siegel’s rendition, all expertly mixed head and chest. I thought I had done an okay job of blending the break between my registers, and making some chest sounds when required. I sang the solo, hands shaking with nerves, and I looked and sounded just like a 15 year old opera singer with an undeveloped chest voice. And so I played the keyboards for "Birdland".

Finally, I got to perform a solo on one of Shillelagh's final concerts of the year. I loved a torch song by Julie London (another breathy chesty singer), called Cry Me A River. But there was no way I could sing those low notes, even with a lot of breathiness and a microphone. So I rearranged the song to make it easy for another pianist to play, and transposed it six keys higher. (SIX keys higher??? *Smacks forehead*)

I took music theory the following year, sang Soprano 1 in choir, and someone else played the DX-7. I played Milly in Seven Brides For Seven Brothers (an alto role!) who never really sang high notes and didn't have to sing beautifully in her lower range, either. I just emitted some chest voice sounds and left it at that. It could have been a golden opportunity for me to start learning how to balance my registers. Instead, I learned how to square dance.

It took me another twenty years to finally learn how to strengthen my chest voice so I could blend my registers and make all kinds of mixes, including a belt sound. Right after I learned to belt, I got an unexpected promotion from keyboard player to solo performer . . . more later.

Teaching Something or Otter

A story from a recent lesson:She is 10. To emulate her favorite country singer, she pinches her throat, squeezes her lips tightly, and tries to carry her chest voice so high she ends up yelling. She looks like she's in pain. She has no idea she is doing this. But her mother knows that something is wrong with the way she is singing, and that is how she ended up in my studio a few months ago.

I know she needs to find a head voice -- the lighter sound you hear in higher pitches. I know from my Somatic VoiceWork training that she has spent too much time in her chest range, like many tweens who listen to Top 40. Her voice is like a barbell with a 100-pound weight on one end only, and nothing on the other. She needs to balance her voice by strengthening her head register. If she does, she will suddenly have another octave or more of notes to work with, and she'll be able to sing with comfort and ease. In short, she'll be lifting evenly and with power everywhere. If she doesn't strengthen her head register, she will severely hobble her vocal range and become one of those singers who say at age 12, "I'm more of an alto."

To access her head register, we make angel sounds on "ooo", and emit whoops and sighs. Some singers can find head voice while singing traditional vocal exercises, but many singers just continue to tense up on anything that sounds like music. So, we take out melody and rhythm and just make a bunch of weird sounds. It's hard to tense up if you're whooping and sighing, and that's the whole point. Then we add melody and rhythm back in, slowly.

She still strains her neck muscles and pulls her mouth into a rhombus shape to reach higher notes, even on an "oo," which means she's not really accessing her head register at all. We push air into our cheeks and say "poom!" in a light siren-y wail as the air spills out, and she laughs and calls it "chipmunk sound." And there is her head voice, light and clear and easy. She has learned to identify it when she feels it (that is a major accomplishment in itself), but she doesn't think she should use it to sing, so at every lesson I have to sell its benefits to her again and hope that she'll buy. In her very limited singing and listening career, she has decided that she must sing chest in order to be heard and in order to be stylistically "correct." Every time she starts to sing, she defaults back to her pained chest sound. She's much more familiar with that and it feels easier just because she's done it more. She has no idea that her idols don't sing that way.

This is when singing lessons become more like therapy sessions. Somehow I have to convince this sweet girl that it's all right to sing with a mix of chest and head registers. She has to identify what those sounds sound like to her, learn how to make them at different pitches, and then analyze her current singing and deduce which register she is using when (chest, 98% of the time, but I can't just tell her, she has to figure it out, too). And then, she has to consciously decide that she wants to change her register because she knows it will sound better. All this, while singing pitches and forming words and looking like an engaged performer.

I imitate her chest voice technique so she can see how bad it looks and sounds. I have her look in the mirror so she can see how she grimaces to make a chest sound. "Should you have to grit your teeth and stretch your lips tight, to sound like your idol?" I ask. I pull up a clip of her idol on YouTube. "Does your idol look like she's being poisoned when she sings?" My student admits that, no, she doesn't. "Well, you do," I say bluntly. "You shouldn't have to work so hard to sing."

"But I don't want to sound like a chipmunk all the time!" she protests. Aha. There it is. She is worried that if she gives up the only kind of singing she knows how to do, she will sound so different as to be unrecognizable. I hear this all the time. It is very scary to be asked to renounce your vocal identity, to be told it is necessary to explore and embrace something that feels so foreign. It never works to say, "this is how you must do it." With adults and teenagers, I compare it to real estate. I say, "You aren't selling your house, you're just buying the lot next door and getting ready to expand." Explained this way, most singers are then willing to try some different sounds, knowing that I am not going to ask them to give up their previous sound -- only add on to it. They can keep their "old" voice and add on some "new" parts, eventually integrating them into a whole. But how to explain it to this sweet, scared girl?

I decide to see if she can explain it to herself. "Let's make some high squeaky chipmunk sounds again," I say. She is still having difficulty, so I grab a wooden tongue depressor and have her place it on her tongue, to feel how it rises and falls. "Do you feel how your tongue goes way up when you are singing higher?" She nods. "Can you keep it from going waaaaaay up, just let it go up a little?" She does. "It feels bigger in my throat," she reports. "And easier." Then we make some chipmunk sounds at lower pitches. "It's not quite the same, is it?" I say. "No, it's not," she reports. "It feels different. It feels lower in my face." We're getting somewhere. "What would you call it, then?" She smiles and takes out the tongue depressor for a moment. "That's a squirrel sound!" she says. "Okay!" I say. "Can you go between squirrel and chipmunk?" And suddenly she is swooping from her highest pitches to the middle of her range, darting down into her chest range and then soaring back up again. I know this means her larynx is moving freely. The tongue depressor is keeping everything in check. I can see her lips are active but not terribly tense. "Do you notice how strong and loud you are?" I ask. She nods vigorously.

Then we make some chest sounds with the tongue depressor in, just for contrast. The sounds are a little lighter now, since she has been spending time in her head register. "What should we call those?" I ask. "Otter!" she says gleefully. She darts between otter sounds, chipmunk sounds, and squirrel sounds. She is a virtual menagerie. If I wanted to bring all this vocal development to a screeching halt, I would just ask her to sing a five note scale. She would sing every note in her chest range, then squeak out a few pained high notes and tell me she doesn't like singing "high" and we would be back to square one. Instead, I suggest something. "Can you sing part of your song in chipmunk and squirrel voice, even with that tongue depressor in? No words, just chipmunk and squirrelly "ooh"s and "ee"s?" She considers my strange request, and then says, "Sure!" Out comes the melody, plus a bunch of other random notes, but they are light and free. "Was that totally squirrel and chipmunk, or did you also sing a little otter?" I asked, knowing the answer." She is thoughtful. "I think it was mostly squirrel and chipmunk. Maybe a little otter."

"I think you're exactly right," I respond, thinking that Miss Berlin at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory Of Music never taught me the Otter Method of Vocal Pedagogy With Tongue Depressor. "Oh yeah, it's like so much easier to sing in chipmunk and squirrel. Totally," she says.

"Now, try a little of the words, but you're still feeling that squirrel-chipmunk feeling, with a little otter on the lowest notes," I say. "With the tongue depressor still in?" she asks, incredulously. "Yep, with it in," I say. "Let's go really slow to give your mouth a chance to get it all together." We sing a dirge-tempo version of the melody. It doesn't work for every note, but it works enough that she is grinning at the end of the song. And her mother, who has been watching, raises her eyebrows in happy approval.

"I don't know how you are getting that sound, but it sounds great, honey!" Mom says. "Now, how am I going to get her to do this at home?" I hand Mom a tongue depressor so we can all feel what our tongues are doing. This makes Sweet Tween giggle even more. "Now make otter sounds, Mom!"

The lesson is over. She has accomplished so much in 60 minutes, and I tell her so. She sings a little bit of the melody, then stops herself. "That was my old voice," she says. "I'm going to sing it with my new voice." From experience, I know that the next time I see her she will sing with her old voice. She will probably start in her chest register. She will need to be reminded of what her head register sounds like and how to get there. But, she has made a great start. She has three animals for reference. She has tongue depressors to help her feel the action of her tongue, and she has a mirror for observation. Best of all, she has a willingness to change, because now she knows it will sound better.

The Seven, Vol. 7: Lung me tender

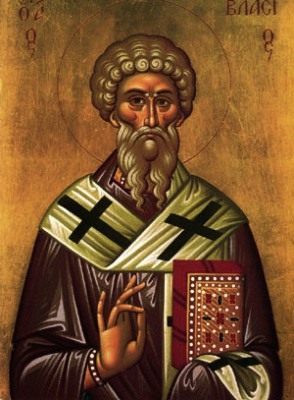

1. So I'm recovering from the flu. No one else in the house got it but me. I'm sure its nastiness was blunted by the flu shot I got last October, but it still got me good: Muscle aches, fatigue, fever, and this damned cough. I have been coughing for over a week now and am having difficulty stopping. You know that awful feeling, when you are trying to stifle a cough but can't? Yeah, that's me all day long. 2. I have tried honey, Prednisone, red wine, hot baths, Mucinex, Maximum Strength Tussin. I'm also hurling prayers to St. Blaise, the patron of throat ailments (he did some miraculous things for a kid with a fish bone caught in his gullet). St. Blaise said he's busy with all the other coughing singers and he'll get back to me. Blaise's feast day is next Sunday, Feb. 2 and I can think of no better way for him to celebrate than to heal my throat.

3. The rest of me is fine, it's just the coughing, and it's keeping me awake at night and tired during the day. I watched the entire miniseries Cranford (it was like watching a long movie treatment of an Austen novel, but with many more deaths). I caught up on New Girl and The Mindy Project (aren't they the same show?), I saw the movie musical Nine (really liked Fergie's performance but not Nicole Kidman's) and Frances Ha (lame). I can't seem to focus much on reading at the moment but I'm trying to get back into my Truman biography and also The Sellout, about the history of the 2008 financial meltdown. I was hoping these heavy tomes would help me sleep. Didn't. The Best Photographer In The World said, "When I can't sleep, I start saying 'God Bless' and start naming everyone I can think of, and it helps." Yeah, he's just a saint, ain't he? I did it, it helped somewhat.

4. My coughs are (ahem) not very productive, but my bronchial passages are so irritated, they just freak out at the first sign of air moving through them. I can feel that squirmy "I gotta cough" feeling as I breathe. I don't even want to THINK about how red my little larynx is right now. I am the singer who should be told to just shut up and rest. But somehow I managed to teach two whole days and cantor two Masses this weekend. I didn't say it was pretty, just said I did it.

5. I thought it was just a bad cold, because it wasn't nearly as debilitating as the last time I had full-fledged flu nine years ago, so I downplayed it. It took me over a week to see a doctor who told me, no, it was flu. If I had realized it in time, I might not have attended the three-day Somatic VoiceWork conference with all my voice teacher peeps. (Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I was careful to quarantine myself as much as possible, and I limited my socializing!) Though I was a bit lonely in my self-imposed isolation and couldn't sing a note, I managed to have fun and as always, I learned a great deal and continued to solidify my own pedagogy. We hear from speech therapists and pathologists, we share techniques and advice, and we practice teaching each other so we can benefit our students back home. Analzying the vocal function of a great singer in front of Jeanie -- whose veteran ears are sensitive to even the smallest vocal changes -- sometimes feels like doing differential diagnosis with Dr. Gregory House. Which is why it's so fun!

My ears get such a great tune-up and when I see my students again, I can make finer and finer adjustments to their singing. That is, when I am not trying to protect them from my coughing.

6. I'm going to try this throat-calming recipe from Dr. Peak Woo. Besides having an awesome name, Dr. Woo is one of New York's most prominent otolaryngologists and a friend to Jeannette LoVetri, our SVW founder and guiding light. He has treated a lot of famous throats and this is his The Gargle Of The Stars: Mix together some saline (6 oz water with 1 oz non-iodized salt); some large sugar molecules (1 T honey, or white corn syrup or glycerin), some baking soda to coat the throat (1/2 t), and a wedge of lemon (to promote saliva). This gargle is safe to drink, but you go ahead without me.

7. We watched some really funny videos on the first evening of the SVW conference, including a hilarious one of some famous Italian opera singers insisting they never, never ever used chest voice. At all. Nada. Then they started singing and proved themselves wrong with every single note. Even better, they were being interviewed by a countertenor who used nothing but head voice! Enjoy, especially if you're a voice teacher. We were laughing so hard, I bet no one even heard me coughing. XO EC