"They want me to sing sixteen bars a cappella," the student says as we start to prepare her for the audition. "What?" I ask. "No pianist?"

"No music at all, just me singing," she says.

What I'm thinking: "But you're auditioning for Fiona from Shrek! In the show you will have to belt high D-flats. How will they know you can do it? As your voice teacher, I know that having the musical score underneath helps you nail those notes. Unless the music director has perfect pitch or has a tuner handy, they won't know if you (or any other singer) can sing the notes the score requires you to sing. This is stupid. I can't believe you're expected to audition a cappella for a show that will have a full orchestra in the pit. That's like signing a baseball player to the team after he walks the bases, or telling McDonald's to cook your Quarter Pounder medium rare.

“So they don't want to pay a pianist for auditions, or they don't have access to a piano in the audition room? Okay. You mean to tell me that no one in your drama organization can figure out how to provide you with a karaoke track to give you at least a little support? Well here, I took 25 seconds and found it on YouTube, and now I'm playing it on my phone at high volume. You can do this at the audition, if they'll let you. Or at least listen to it right before you go in. Definitely buy a chromatic tuner app, which can give you a secure starting pitch.

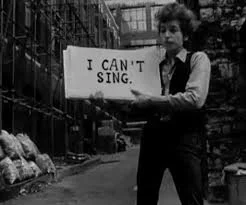

“I don't blame you, student. I blame American Idol and Pitch Perfect, which have made a cappella auditions seem cool. In fact, a cappella auditions are often terrible and they make iffy and nervous singers sound horrid. Even professional singers can sound slightly unsupported and shaky in an a cappella format, without the bass line and melody of the score to balance out the voice. Most amateur singers don't know how to edit a song for a cappella performance. The singer continues to "hear" the melody of the accompaniment in their heads and they unwittingly include it, but the auditioners only hear awkward silence, and that ruins the energy of an otherwise good audition. Who thought this was a great idea for less experienced kids and teen singers?

I can't believe that in addition to teaching notes and rhythms and performance skills, I now have to teach you how to sing an accompanied song unaccompanied, just because someone thought it would be "easier." I just have to cross my fingers and hope that you sing the correct pitches in your audition. It stinks because I know that pitch accuracy matters, every time you open your mouth. Ultimately you will be singing with accompaniment, so you have to sing what's written. But your auditioners won't know if you're accurate or not (or if anyone else is, either). You could be vocally perfect for this part and sing a flawless audition, but you could easily lose out to someone who actually can't sing the role at performance time. GREAT IDEA, A CAPPELLA."

What I say: "Okay, here's your starting note. Go."

My video on how to nail an a cappella audition.